Chapter One.

Raspberry Jell-O.

Ro to Mahalia Thomas.

Ro to Mahalia-come in, Mahalia! Call me, Hallie. Write me. Send me an

e-mail. Do something to let me know

I’m not in the twilight zone!

I

squinch my eyes shut and send Hallie a mental message, just like we agreed. Call Ro. Call Ro. Call Ro.

And

does she call? My best friend since our diaper days? Does she sense my misery

and come rescue me?

Does

she what. Zip. Nada. Zilch. Not a whisper. Not so much as a tremble in

cyberspace or a quiver in the ether.

Thanks a lot, Hallie. I owe you. Not. Don’t forget some of this is

down to you.

I

open my eyes again. I look about. Same old, same old.

I sigh. Get over it, already! So you’re stuck in a village at the butt

of the world. It could be worse. (So I tell myself.) You might be hiking through

a tick-infested jungle. You might be stuck in summer school. You might be

flipping burgers at Greedy Gus. I crank another sigh. I could go a burger, or a

chilidog right now. I could swallow any diet-buster with a thick shake chaser.

Gaining a few pounds then losing them again would give me something to do.

Something aside from fret about the boy I met downunder.

Boys, who needs them? I used to say to Hallie.

And

Hallie’d give me the big eye-roll and tell me; We

do, Ro! What are you like?

“Hey,

honey.” Mom’s voice breaks in on my thoughts. Mom’s smile pours over me,

sweet and slow as molasses. Mom’s as happy as a honeybee tucked up in clover.

All her spiky edges have smoothed right down. She loves it here in Tasmania.

It’s

so quiet, she says. Just the place to soak up atmosphere, and work on her book. And to rest and prepare for seminars and lectures when this

brief vacation is over.

And

I say; she’s not wrong about that.

It’s

peaceful, she says. It’s so beautifully predictable, she says.

She’s

wrong there, though. Is she ever wrong about

that one.

“Listen

up, Mom,” I said, the first time she mentioned the P-word. (The

P-for-Predictable, that is.) “You might be able to predict the weather, or

that every time you open your mouth someone asks if you’re an American. You

might even predict all the magazines at the Laundromat will be two years old and

have the crosswords all filled in with ink. But you can’t predict-”

My

voice broke off at that point. Just snapped off like a rotten old twig.

“Can’t

predict what, honey?” asked Mom.

“You

can’t predict-” My voice did it again. I struggled. I really did. I opened

my mouth and wrapped my tongue around the words I meant to say. It was like

talking through a mouthful of raspberry Jell-O.

“…can’t

predict…?” Mom actually took off her shades and turned to stare at me.

“You can’t predict what, honey?”

“You

can’t predict P-people,” I said,

lamely.

That

wasn’t what I wanted to say, but it was all my mouth could manage.

What

I meant to say was that you couldn’t predict Patrick. I wanted to

say that no one could have predicted when and where I’d be meeting Patrick

Carroll.

There!

I said it. I thought it, anyway. If I close my eyes again, maybe I can bring him

into focus. Maybe I can pin him to the sky like a butterfly on a board, like a

shimmering mirage.

Ro to Patrick. Ro to Patrick. Come in Patrick Carroll. Come back from

wherever you went so we can fight some more.

The

sky is the blue of the dress Mom wore to the Prom a million years ago. There’s

a wisp of cloud like the stole she had over her shoulders.

And

Patrick isn’t there. Not on the clouds, not in the sky, not standing in front

of me gripping my hands as if he’d drown without me. Not laughing and giving

me the kiss-that-didn’t-miss.

“Patrick,” I whisper. “Oh, Patrick.

Please come back.”

“What’s

that, honey?”

Patrick.

But

the word never leaves my mouth. I try to mention him to Mom. I struggle to say

the name. It’s raspberry Jell-O time again. And now it isn’t fair. Now that

he’s gone, why shouldn’t I say his name?

“Ro,

are you all right?”

“Yes,”

I said, but it’s a lie. “Just a tickle in my throat.”

“Fix

yourself some juice,” suggests Mom.

But

drinking juice won’t fix what’s wrong with me.

“Patrick.” It comes as the tiniest whisper. Mom doesn’t lift her

head.

“But

Mom, since when were you going downunder?” (That was me talking,

back in early December.)

“Hey,

honey…” (Mom’s sweet slow smile came out to play.) “Since Dr. Craig’s

pickup had a fight with that semi. That’s since when.”

“But you can’t just go to Australia instead of

Dr. Craig!”

“Why

not? Wilf’s finalized all the arrangements. Wilf says we can take over the

apartment Dr. Craig was planning to rent.”

Wilf!

I thought darkly. What sort of man calls himself Wilf

these days? The name sounds like he should be a hundred years old, but Wilf

Porchetto is no more than thirty. Wilf is Mom’s agent as well as Dr.

Craig’s, and he’s so sharp he’ll cut himself one day on his own clever

notions. And Wilf thought Mom could go to Australia because Dr. Craig was in

hospital? What was this; Mix and Match?

“Haven’t

the downunderites got their own educationalist behaviorists?” I asked. (An

educationalist behaviorist is what Mom is. Don’t ask me exactly what she does.

And don’t ask me why I’m not a straight-A student. You know what they say

about shoemakers’ children never having shoes.)

“I

guess not, honey.”

“Of

course they have,” I said sharply. Mom’s honeying was making me feel like

sucking a lemon. “You’ll get there and no one will hire you, Mom,” I

warned.

“I’m

hired already, remember?” said Mom smugly. “And in my free time I can work

on my book.”

“Dr.

Craig was the one they hired,” I corrected her.

“That’s

right, honey, but I’m just as qualified.” Mom shrugged. “I know this is

kind of sudden, and if you don’t want to come I’ll understand. You could

stay with your Aunt Vida, honey.”

And

share a room with Doughy Chloe? Listen to her wheeze the night away because she

can’t stay away from Dunkin’ Donuts?

“I’ll

stay with Hallie,” I said.

Mom

frowned just a little. I saw the kind of squinch between her eyes. “Not in a

two room apartment, honey. If you come with me, you can do a year of high school

in Australia. Their school year starts around late January.”

I

sucked my lip, thinking about that. Go to high school away across the world,

thousands of miles from all the kids I’d known since elementary school? I’d

gone through junior high with them–Beth Anne, Hallie, Josh and Alex, Shonee,

Tav and Tedson Wallace the Third. There were others too, but those were the ones

that mattered.

“What

do you say?” asked Mom. “It’ll be an experience.”

And

you get to see the Australian education system from a parental viewpoint, I

thought. Good one, Mom.

“Why

not?”

Mom

smiled lazily.

I

know when I’m being played for a sucker. I’d put in a couple months at

Woodbrock Senior High, and it wasn’t much different from the Junior Campus. I

thought a school downunder would make a change.

I

was right.

“What

about you and Alex?” my best friend Hallie wanted to know. That was after

she’d called me a purple-toned rat for going off without her for so long.

“I’ll be all alone!” she wailed.

“As

if,” I said. “You’ll have-” I paused, then we both chanted; “Beth Anne

and Josh and Alex and Shonee, Tav and Tedson Wallace the Third.”

Hallie

rolled her eyes, right around in her head, like peeled black grapes.

“They’re OK, but they’re not my best bud. And little old Tedson still

isn’t speaking to me. And what about you and Alex?”

“What

about me and Alex? There is no ‘me and Alex’.”

“No?

He’s got the biggest crush on you.” Hallie stretched her hands out wide.

I

pushed my bangs out of my eyes with both hands, and wished I could push the

sudden red out of my cheeks. “Get over it, Hallie! Where did that come

from?”

Hallie

looked me straight in the eyes. “Would I lie to you?”

What

Hallie said weirded me out. Alex is a computer nerd, with zits. (Why do nerds

have zits?) But he’s kind of cute. His mom says Alex would never date a girl

without a built-in modem. Guess his mom is wrong, if Hallie is right.

Hallie

grinned, flashing her retainers at me. “You’re blushing,” she crowed.

“Rowena Maven’s blushing!”

“As

if!” I put my hands over my cheeks. “If I am, it’s because I’m mad. No

fair,” I added. “You can blush and who’d know?”

Hallie

smirked, and punched the air. “Black rules!

You ought to see his screensaver.”

“Why?”

“What

would you care?”

By

now I was getting mad. I thought she was winding me up because I was going

downunder and leaving her behind in little old Woodbrock.

“I

don’t care,” I said coldly. “You brought the subject up, if you recall.”

“He’s

got that picture of you from the Junior High yearbook,” said Hallie. “It’s

set to come up after an idle ten seconds.” She grinned. “Guess he leaves it

idle quite a lot.”

“The

one of you and me eating cotton candy? Yeuch!”

“I’m

not in it any more.” Hallie turned down her mouth. “He scanned me out. And

guess what he scanned in where I used to be?”

I

didn’t guess, so Hallie told me anyway.

“A

little old candy heart.”

“Yeuch!”

I said.

“Hey,

forget it. I bet you’ll meet some cute guys in Australia.” Hallie winked.

“Pack your bikini, Ro.”

“It’s

forty degrees,” I pointed out. “I’d have goosebumps on my goosebumps.”

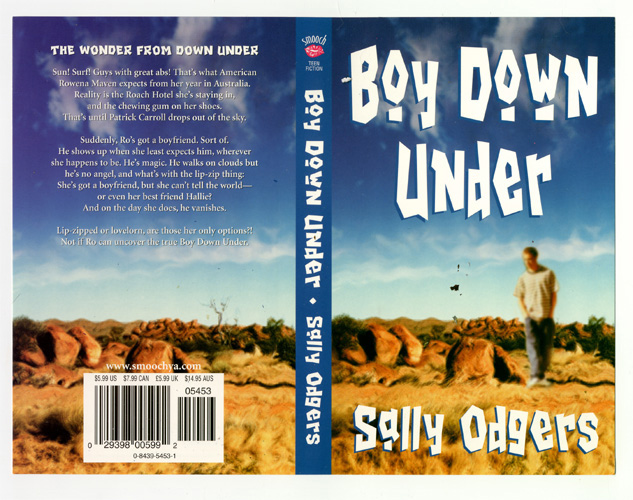

“Australia’s

hot, and it’s full of hunks. They all swim laps before breakfast, and

they’ve got bodies to die for. You see it on TV.”

I

tossed my head to show I wasn’t interested in bodies to die for. But still, I

packed my bikini. I might have goosebumps that had just gotten past a training

bra, but heat makes things grow, right? A year in the tropics and my lemons

might be melons.

Dream

on, Ro, I thought.

And

while you’re at it, dream of the boys downunder.

Hallie

called me up that night. “Hey.”

“Hey

yourself,” I said. I was still kind of sore at her.

“I’ll

call you,” said Hallie.

“You

just did.”

“When

you’re in Australia. I’ll call you. If my mom will let me.”

“Telepathy’s

cheaper,” I said. (I’d seen Mom’s telephone bill after she’d been

putting calls through to Australia.)

“You

telepath me, then,” ordered Hallie. “Every single day.”

“Every

single day,” I agreed. “I’ll send you a mental message.” I hummed a

spooky tune down the telephone.

“You’d

better,” said Hallie. She put on a voice like Ms. Fellows at school. “You

must make an effort, Rowena, if you expect results!”

I

laughed. Hallie always cracks me up when she isn’t driving me insane.

“Sure!” I promised. “I’ll send you mental messages and you’d better

answer, Mahalia Thomas.”

“I’ll

do better than that,” said Hallie. “I’ll get Mom to enter those TravelSure

promotions and win her a little old trip to Australia. She can send little old

me.”

We

laughed about that. Hallie’s mom is always entering competitions. She clips

coupons, she writes slogans, and she’s a genius with 25 words. She and Hallie

joke about it, but the spooky thing is, she quite often wins! That’s how she

came to be doing Pilates class while Hallie and I talked on the phone.

Getting

ready to leave was kind of unreal. Mom saw to all the visas and paperwork, and

Wilf kept calling and sending her more contacts, brochures and bookings. Mom

stuffed them in her briefcase. She hardly seemed to look at them, but I knew

she’d be ahead of the eight ball. Mom seems slow and sweet and lazy when

she’s in Mom-mode, but when she steps into Dr. Marina Maven-mode she kicks

butt. It’s like she becomes this totally other person, three inches taller and

ten pounds lighter.

I

used to think Mom was the only one who did the chameleon trick. Because of

Patrick Carroll, I know better now.

Back to - chapter 1